|

What is graphic medicine and how can it help increase the low health literacy rates seen globally? The term “graphic medicine” is broad, but Dr. Ian Williams defines graphic medicine as “the intersection between the medium of comics and the discourse of healthcare” (Czerwiec et al.). It is “comics meets health care” and a useful tool to teach health literacy, which allows healthcare recipients to make more informed decisions. Global health literacy rates are low, and the United States is no exception. Only 12% of adults aged 16-65 years achieved the highest literacy proficiency level on a scale of one to five (Centers for Disease Control). Graphic medicine as a health literacy tool is affordable and easily obtainable, crosses barriers of language and literacy, and entices reluctant readers. Learning from text plus pictures, graphic games, and other graphic medicine materials may also offer improved memory recall and retention rather than traditional text alone.

Though the term graphic medicine originated in 2015, using comics in health care began long before. Though not yet widely used as a health literacy tool, health educators have used graphic medicine for decades, such as drawing funny cartoons for patients or using comics to explain a procedure. Historically, comics were considered children’s reading. However, evidence suggests adults may also benefit from learning through graphic medicine. The multiple mediums that graphic medicine represents may be one way to teach health literacy and that is just what health educators are doing globally in the 21st century. A study using comics in pediatric and adult electronic health records (EHR) revealed increased interest in their EHR (71-71.6%), long-term memory recall of seeing the comic (90-100%), and recall of at least one best-practice behavior from the comic by almost half (42-46%) of the participants (Alkureishi et al.). Using graphic medicine as a teaching tool for medical students also shows promising results -- students reported using comics increased empathy and reduced feelings of burnout (Sutherland).

Graphic medicine allows for the use of pictures and text, which can increase perception, interest, and empathy, as well as decrease feelings of isolation. It may cross language barriers seen in traditional text alone. Educators and librarians have a vast array of materials to choose from or create. For example, to teach about cancer and social dynamics, About Betty’s Boob offers mostly pictures, which can cross language and literacy barriers. When David Lost His Voice teaches about terminal cancer, family dynamics, and coping with the impending loss of a loved one. First Year Out provides an in-depth glimpse at the emotional and physical challenges people face when undergoing gender transitions. Infertility and pregnancy challenges are the focus of the autobiography Kid Gloves: Nine Months of Careful Chaos.

Children enjoy superheroes and comics, but when struggling to understand an illness, comics can provide a respite from medical jargon and relieve stress. Medikidz offers a variety of works about pediatric illnesses and health challenges. These can often help teach parents, especially if there is a language or literacy barrier. Autism, diabetes, epilepsy, organ transplants, hospital stays, sleep apnea, chronic pain, and a plethora of topics provide explanations for younger audiences. Younger children may benefit from these works, even without literacy skills. As graphic medicine grows globally, its availability in multiple languages grows as well. Mi Padre Alcohólico es un Monstruo (My Alcoholic Father is a Monster), Supersorda (El Deafo), and AIDS - Why did the Boy Die? are Spanish, Italian, and Japanese graphic medicine, respectively.

Not limited to books, graphic medicine takes other forms. All ages may enjoy making a comic book based on health issues they experience or experience with loved ones. Zines are easy-to-make mini-comics. Websites offer instructions and videos to help educators learn how to offer these for a health literacy activity. Educators might use graphics from online resources or software to create fun, easy-to-read manga or comic-inspired infographics or posters. One-page infographics are affordable ways to increase health literacy. These are relevant at health fairs, in classes at all levels, or in the medical environment.

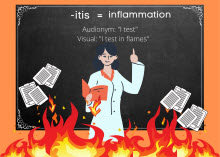

Learning medical terminology is not the simplest for students or patients. Using comics and cartoons to create audionyms adds a fun, yet informative way to learn difficult terms. Websites publish educational graphic medicine as well. Graphic Medicine offers reviews, podcasts, databases of works, and much more and is useful for the novice educator as well as the expert in graphic medicine. Annals of Internal Medicine has over 200 web comics in Annals Graphic Medicine to help teach about a variety of healthcare topics. The National Library of Medicine created “Graphic Medicine: Ill Conceived and Well Drawn,” a collection of teaching resources and exhibits about using graphic medicine in the classroom. They also offer videos about using graphic medicine to teach health literacy. A YouTube search using the keywords “graphic medicine” offers viewers recorded presentations and lectures, as well as special videos on making comics in the classroom or healthcare setting.

The benefits of using graphic medicine to increase health literacy are affordability, age-level customization, a first-person perspective missing from traditional medical texts, the ability to cross language barriers, and increased perception and memory recall. Try buying 10-12 relevant titles, hosting a zine event, or making graphic bookmarks at your next health event. You may be surprised at how well patrons of all ages receive it.

References

Alkureishi, Maria, et al. “Impact of an Educational Comic to Enhance Patient-Physician-Electronic Health Record Engagement: Prospective Observational Study.” JMIR Human Factors, vol. 8 no. 2, 2021, https://doi.org/10.2196/25054.

Bell, Cece. El Deafo: Spanish Edition (Supersorda). Maeva Ediciones, 2017.

Cazot, Vero. About Betty’s Boob. Archaia, 2018.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Understanding Literacy and Numeracy.” Health Literacy Basics, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/learn/understandingliteracy.html

Czerwiec, MK, et al. Graphic Medicine Manifesto. Penn State University Press, 2015.

Kibuchi, Mariko. Mi Padre Alcohólico es un Monstro. Fandogamia, 2021.

Knisley, Lucy. Kid Gloves: Nine Months of Careful Chaos. First Second, 2019.

Yoshihiro, Saegusa, and Ryuichi Hirokawa. AIDS-Why did the Boy Die?. Kodansha, 1992, 43-44.

Sutherland, Travis, et al. "Brought to Life through Imagery-Animated Graphic Novels to Promote Empathic, Patient-centred Care in Postgraduate Medical Learners.” BMC Medical Education, vol. 21 no.66, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02491-4.

Vanistendael, Judith. When David Lost His Voice. SelfMadeHero, 2013.

DCT Featured Article - September 13, 2022

|